Do Big Tech companies exploit our data? This belief is so universally accepted at this point that it seems somewhat silly to even question it. The subject is a central theme in the popular anti-Big-Tech Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma, and a common rallying cry of pundits and politicians.

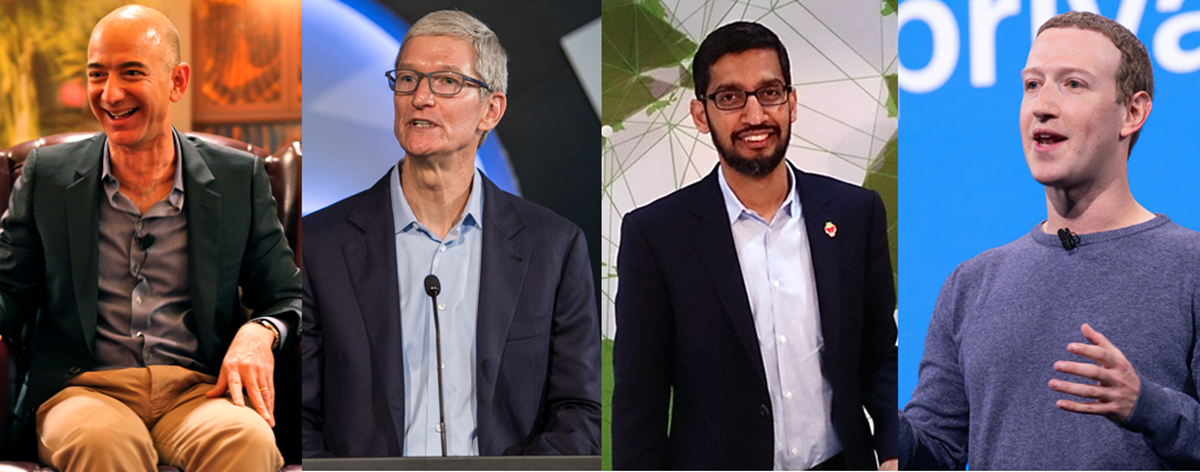

The idea that perpetuated in the film (and in broader popular discourse) is that companies like Facebook, Google, Amazon and Apple are harvesting a valuable possession from us, the same way a fraudster cons an old lady into unknowingly giving up her life savings.

The logical implication that follows from this frame of thought is that if naive consumers are being conned out of our precious data, then tech companies need to “pay us back” in order for justice to be served. The political ground is ripe with opportunities for politicians to help consumers obtain our “due compensation”.

Indeed, popular tech author Jaron Lanier argues that consumers should demand to be paid for their data via micropayments. In the legislative arena, perhaps the most prominent policy effort has been undertaken by Californian policymakers. Backed by Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, California launched a “Digital Dividend Project” that seeks to help consumers gain “their fair share” for their data. This intuition that “our data should belong to us” also forms the driving impetus of data localization laws that national governments everywhere in Asia, Europe and the U. have enacted in recent years.

The problem is that this train of thought is inconsistent with the economics and reality of data usage. The popular notion that Big Tech companies are simply sitting around, picking up our data on the Internet “for free” and then proceeding to profit off them at our expense, the same way a thief waits under the apple tree of a private orchard garden and makes off with fruits of somebody else's labor, is dead wrong.

Apples require that one spends time, effort and monetary investment to nurture and grow in order for it to have value. Similarly, intellectual property that companies spend millions in R&D to produce has value only because organizations have undertaken the effort to create a valuable asset.

On the other hand, what we refer to as “data” are micro bits of information about ourselves that are not only cheap and worthless by themselves, but can be easily reproducible and given to different entities. As Alec Stapp points out, data are an experience good, which means that its asset value depends on how it is merged with other datasets and deployed in the right contexts. Its value cannot be predetermined in the same way we can estimate the value of a basket of apples based on the existing demand and supply of apple markets.

Therefore, rather than thinking of our data as being “stolen,” the more appropriate economic explanation is that tech companies have successfully engineered a way to make use of previously-unused resources to create value.

Moreover, it is not clear that users have the rightful “ownership” over much of the data that critics complain Big Tech controls. Even if we can agree that data like our names, ages, and birthdays rightfully “belongs” to us, what about interaction data, such as me listening to the latest indie rock music on Spotify, or my friends “Liking” my latest status updates?

In the absence of Spotify, we would not know what the “Most Played Indie Hits” are. Without the social communities that Facebook, Twitter and YouTube allow me to connect with, I would not have written a post or posted a video, and therefore the data of people “Liking,” commenting, or resharing my content would not exist at all.

Not only would these types of data not exist, a good argument can be made that these data are the rightful intellectual property of these firms. To store and crunch these data for insights, tech companies invest billions of dollars in cloud storage and data analytical tools. A 2018 Wall Street Journal report finds that Amazon, Google, Facebook and Microsoft rack up one of the highest capital expenditures, of which “most of this spending goes toward the state-of-the-art data centers used to power their services”.

Taken together, what this means is that the big villain narrative that Big Tech corporations harvest our data before selling them for a quick buck without any input or investment on their end is simply false.

Anti-tech pundits frequently complain about the “costs” of giving up our data, and to be fair, tech companies do sometimes handle our data suspiciously. Yet these takes almost always neglect or gloss over the “benefits” side of the equation.

Take YouTube for example. The reason YouTube has billions of users in monthly traffic today and overwhelmingly dominates viewership in younger demographics is in no small part due to the fact that its data-powered ecosystem is brilliant at recommending the right videos to its users (a way to test this is to compare the time you spend watching videos that you search for versus suggested videos).

Similarly for Google, its search engine reigns supreme because it is exceptional at returning ranked web results to users based on the insights of aggregate data that show trends in what users are collectively searching for. It is not at all a coincidence that we almost always find what we’re looking for on the first page of Google results—that is billions of dollars worth of data analytics at work.

With Facebook, Instagram or Amazon, our data are used to train their algorithms and artificial intelligence tools that are constantly running in the background and enhancing our overall user and shopping experience. For social media platforms, this translates into users seeing more posts and news from our preferred people and sites, and less content that we find distasteful or plain annoying.

It also helps advertisements be more targeted and relevant. For example, Facebook provides its analyzed data to marketers on its platform, empowering businesses to locate and sell to their target segments. With Amazon, consumer products and goods that align more to our preferences are getting recommended to us, saving us time in search and discovery, while giving consumers the means to perform quick comparisons across different brands and products.

On tech platforms like Uber, a well-trained algorithm means finding a cab ride at the best possible price and shortest time. On Tinder, it’s the difference between finding the love of your life and having a bad date. Data are essential fuel in the engine of tech companies, used to power and continuously improve their products and services, delivering huge efficiency gains for consumers.

Yet having the data is only step one. Step two involves mobilizing the data effectively through the use of analytical tools and algorithms, which requires human capital, management processes, organisational capacity and an innovative culture. That is the central value that tech companies provide to consumers. A tech company with all the data advantages in the world is still susceptible to failure if it fails to innovate. (Case in point: MySpace.)

The accusation that Big Tech is guilty of exploiting consumers because they use our data to make better stuff can be similarly levied against all corporations in the pre-internet era, who spent millions in R&D to survey and understand consumer preferences in order to do similar things. The difference today is that computers allow us to do data mining more seamlessly, thereby blurring the boundaries of consent and inducing the nefarious afterthought that we are being manipulated.

Of course, this is not to say that the use of data to improve product efficiencies must take absolute precedence over concerns of data privacy. As long as some consumers value privacy, there will always be entrepreneurs serving these market segments, evidenced in the emergence of encrypted chat messaging platforms like Telegram or Signal, or the nudge toward privacy-oriented ecosystems as seen with Apple’s business strategy in recent years.

But privacy is only one aspect that consumers care about, others being cost, efficiency and variety. Legislations and regulations to curb data collection or usage in the name of “data privacy and rights” therefore ignores the multifaceted dimension of consumer preferences while privileging one aspect over all others.

Because much of the tech products and services we enjoy are made possible through the use of our data, these proposals inevitably come at the price of hampering the innovative dynamism of tech companies and therefore consumer welfare. And the worst case scenario is that we increase the entry barriers to tech so much that it deters the coming of the next Facebook or Google.