Last week, gas prices in the US reached an all-time high. There are several reasons for this. Gas prices have been rising for months along with the prices of other goods due, in part, to the massive increase to the supply of money.

But gas prices have outpaced the price increases of all other goods, and the source of recent hikes is clear. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent embargoes enacted by the US government have decreased the available supply of gasoline, leading to higher prices.

These price increases hurt. They were hurting Americans even before Putin invaded Ukraine. My own family has had to revise our monthly budget several times over the past few months to account for rising gas prices. We certainly shouldn’t minimize the pain this is causing for Americans–especially poor Americans in rural areas.

Despite all this, I am optimistic that in the long run, this pain will go away. This optimism doesn’t stem from my confidence that Putin will convert to pacifism or that Biden will adopt the slogan, “drill, baby, drill.”. Instead, I’m white-pilled on gasoline because I have faith in market forces.

To understand why, consider one of the most famous bets of the 20th century.

The Bet

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, ecologist Paul Ehrlich warned the world the end of humanity was coming because we were running out of resources. Ehrlich made all kinds of fantastic predictions including, for example, that “England will not exist in the year 2000.”

Surprisingly, Ehrlich’s ideas were well received. His book The Population Bomb sold over two million copies, and he was so popular that he appeared on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show.

Taking Ehrlich to task on these apocalyptic predictions, the economist Julian Simon challenged him to a simple bet. Simon argued that if Ehrlich was so sure we were running out of resources, he’d be willing to wager the price of some group of metals (a scarce resource) would be higher after 10 years. Ehrlich agreed to the bet and, 10 years later, mailed Julian Simon a check for $576.07.

How did Simon win? How did the price of metals fall despite them being mined and used for a decade? The reason the price of metals fell is the same reason I’m optimistic about the price of gasoline falling.

The Beauty of Spontaneous Innovation

My confidence in markets stems from my confidence that the participants are self-interested. Consider what higher gas prices mean to companies in the industry. They can make more money on each barrel of gas sold. This encourages companies to do several things.

First, it encourages them to drill for more oil. When gas prices are lower, and therefore there is less revenue per sale, it doesn’t make sense for companies to take on large costs to produce.

Companies choose to use the productive inputs that give them the most bang for their buck. But once those inputs are employed, the company has to use more expensive or less productive inputs to produce more oil.

It isn’t until prices rise and oil production becomes more profitable that supplying a larger quantity of oil becomes cost-efficient.

This alone won’t lower prices, but it isn’t the only thing higher prices encourage.

Higher prices also encourage companies to search for new technology and new methods of producing gasoline. In other words, higher prices lead to an incentive to improve technology. This has happened several times in the gasoline industry.

Fracking and shale oil production are two techniques developed in the 20th century which allow for more gasoline production than before. Higher prices and profits can drive similar innovations which will increase the supply of gasoline and lower prices.

Here, environmentalists may be worried, but wrongly so. Higher gas prices also means there is an incentive to develop alternatives. For example, as gas prices rise, the return on developing an affordable, efficient electric car also increases.

I’ve already had at least one person I know say they’ve bought a Tesla in response to gas prices.

And this innovation doesn’t only help people rich enough to buy electric vehicles. As more people switch to electric vehicles, the demand for gasoline falls. This lower demand for gasoline means lower prices!

So, by encouraging businesses to develop new production technologies and develop alternative forms of transportation, higher prices will ultimately give way to prices permanently lower than they otherwise would have been. Julian Simon won his bet by understanding that over a decade, increased metal scarcity would stimulate innovation (which Simon called “the ultimate resource”) and lead to increased technological innovations which would ultimately make metal more plentiful.

Again, this is not a claim that everyone wins. There are some people today hurting from gas prices going up who may not be helped enough by lower future prices to offset their current problems. But there certainly is some hope.

Will the Government Stifle Innovation?

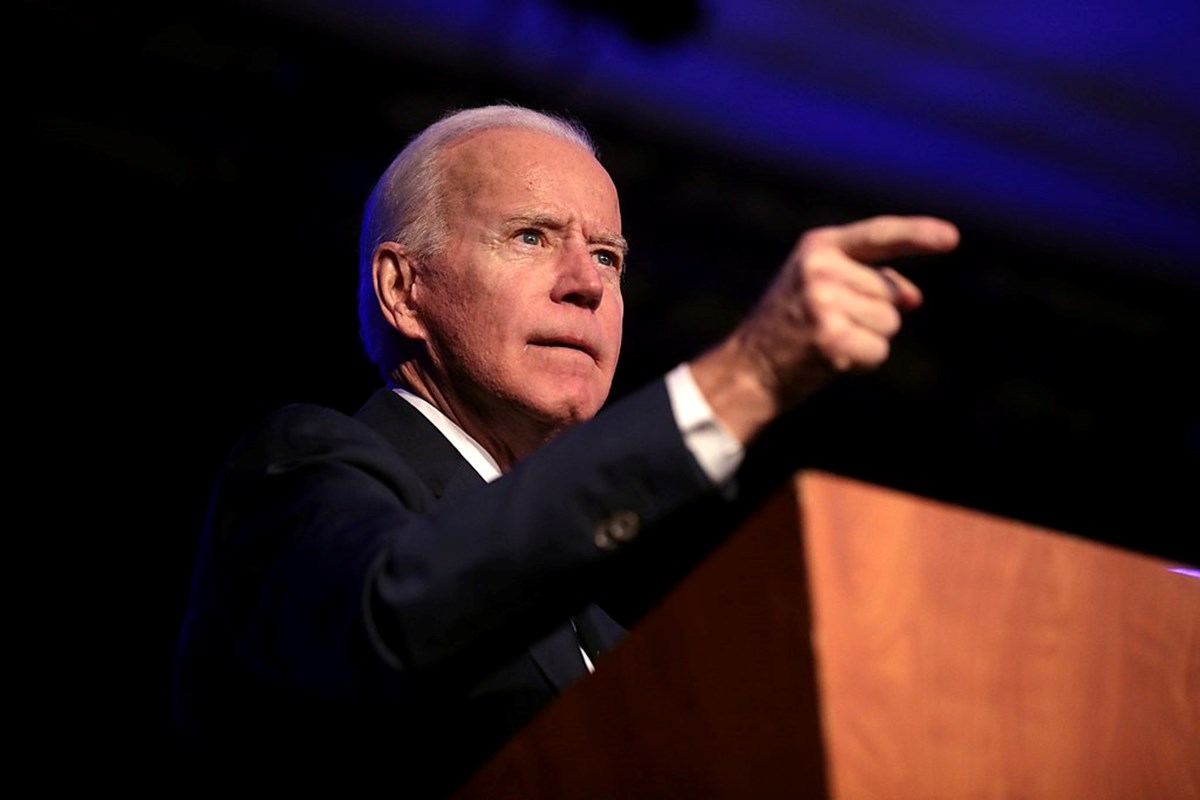

It’s no secret that the Biden administration has taken steps which have hindered domestic oil production. This doesn’t mean Biden has exclusive blame for this (the money printing began before he took office), but he isn’t guilt free.

The administration has denied this, citing the over 9,000 unused permits for drilling. This argument, however, doesn’t hold water for several reasons.

First, the fact that 9,000 permits have been approved by no means implies that the best or most productive oil sites have been approved. Different geographies hold different potentials for profit. Drilling in new places is expensive and requires some time to start up.

We would expect that companies would be very urgent about drilling in the most profitable oil fields, and less urgent about drilling in less profitable places.

So are the 9,000+ approved permits the most profitable locations? I doubt it. It seems likely that political incentives and special interest groups drive much of the decision-making about drilling permits. There is simply no reason to expect these incentives to line up with market incentives.

Even if these permits were the most profitable locations, this still wouldn’t imply politicians have left markets unhindered. The profitability of every new location is dependent on the taxes and other regulations on drilling. The higher the taxes or more cumbersome the regulations, the less profitable it is to drill. And the less profitable it is to drill, the less urgent new drilling becomes.

So the government can hinder the market and innovation, but will it do so in the long run? I don’t think so. Higher prices signal increased scarcity. As scarcity grows, people's willingness to pay for innovations rises.

And, as we’ve seen, this willingness often translates into political dissent. Even before Putin’s invasion, Biden was being grilled on higher prices–especially for gasoline. In my own Kansas town, as in others, gas pumps were covered with small stickers of Joe Biden pointing to the gas price with the simple caption, “I did that!”

If the last few months have reminded us of something, it’s that Green policies based on end-times fears are not popular when the rubber hits the road. Politicians who favor anti-production and anti-pipeline policies will have trouble in the voting booth once the policies are linked to $5-gallon of gas.

Likely this democratic response will be decried as populist when it comes, but it seems inevitable it will come.

So, even considering the tendency of politicians and bureaucrats to try to strangle innovation, I’m confident that the innovation of the market spurred on by price signals will overcome today's high prices.

In fact, like Julian Simon, I’d bet on it.