Aside from a few writing manuals, the book assigned in more college classes today than any other is Karl Marx’s The Communist Manifesto. This is a problem.

Aside from a few writing manuals, the book assigned in more college classes today than any other is #KarlMarx’s #CommunistManifesto. This is a problem. pic.twitter.com/f0bpb36wq0

— Jon Hersey (@jon__hersey) September 1, 2021

Studying The Communist Manifesto and the things it led to in practice is monumentally important to understanding the history of the 20th century—not because communism worked, but because it was so destructive. College students ought to learn what ideas animated Russia’s Bolshevik Revolution and led to the deaths of tens of millions under Lenin and Stalin. They ought to learn what ideas precipitated Mao’s “Great Leap Forward”—and thereby caused the deaths of tens of millions of Chinese people. They ought to hear how these ideas inspired Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge to kill millions of Cambodians. It is urgent that students learn that those acting on Marx’s ideas killed roughly 100 million people during the last century. It is vital they know that those continuing to act on The Communist Manifesto today are still racking up communism’s death count.

But this is not the focus of most lessons on Marxism. Insofar as professors endorse Marxist presuppositions and prescriptions, they do their students—and the world—a tremendous disservice.

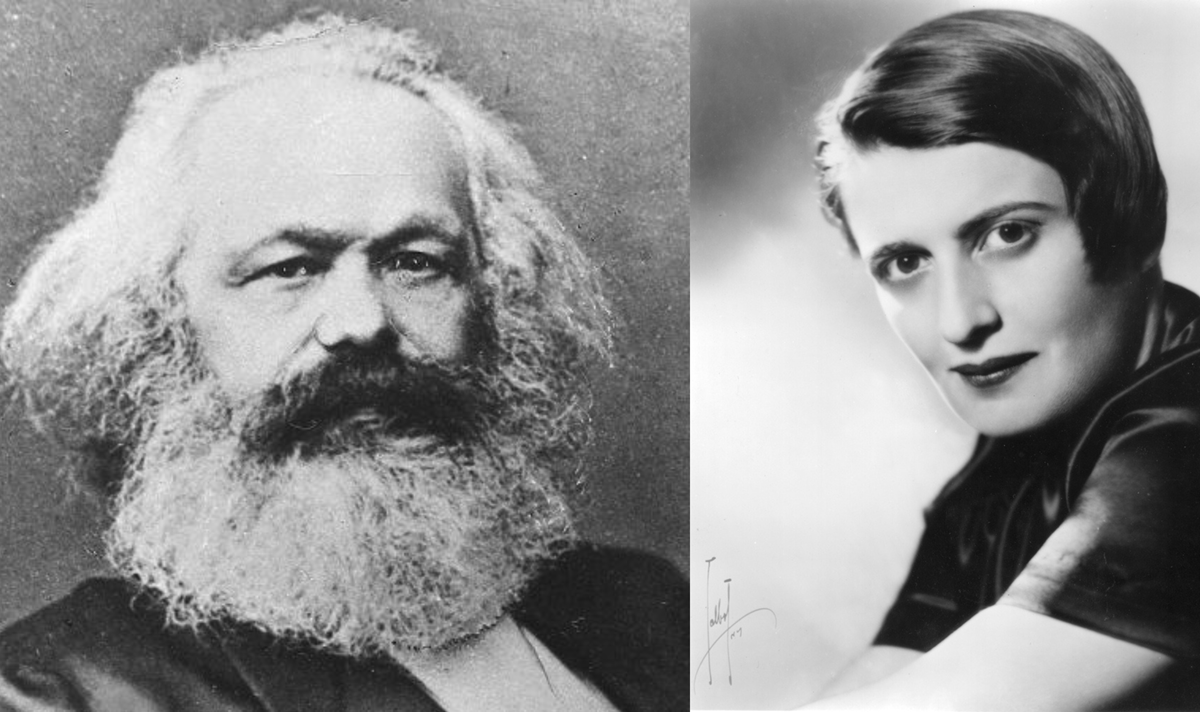

If professors want to prepare students for the real world, they should continue teaching The Communist Manifesto. But they should teach it alongside a book that empowers students to see its grievous faults—Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged.

Con Artists or Capitalists?

Marx argued that those who fund and lead productive enterprises—whatever fruits such enterprises bear—are, ever and always, exploitative and bad. One problem, wrote Marx in The Communist Manifesto, is that these “bourgeoisie” or capitalists push people around by grabbing the reins of government.

Each step in the development of the bourgeoisie was accompanied by a corresponding political advance of that class. . . . the bourgeoisie has at last, since the establishment of Modern Industry and of the world market, conquered for itself, in the modern representative State, exclusive political sway. The executive of the modern state is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie.

Rand agreed that some people exploit others and so are morally reprehensible. But she distinguished between cronies who use political power to wrest money and goods from their rightful owners and true capitalists who engage with employees and customers on a voluntary basis to create the products and services that enable people to live and thrive. The former are the villains of her famous novel Atlas Shrugged; the latter are its heroes.

Rand showed that the root of exploitation is not the profit motive, as Marx thought, but the fact that, in a mixed economy such as we have today, some people are allowed to use government power to violate the rights of others.

A truly capitalist society—based on the principle that all people have equal rights and none may violate the rights of others—bars cronies, lobbyists, and bureaucrats from using government force to exploit people. This, Thomas Jefferson said, is “the sum of good government”—“a wise & frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, & shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned.”

But the more power that bureaucrats have to intervene in people’s lives and violate their rights, the more people will lobby government to protect themselves or attain unearned wealth. Government power—not the profit motive—drives exploitation.

Moreover, bureaucrats tend to use government power to increase government power. Atlas Shrugged illustrates how this works.

For instance, after deciding “it was unfair to let one man hoard several business enterprises, while others had none,” the book’s villains pass the “Equalization of Opportunity” law, making it illegal for “any person or corporation to own more than one business concern.” After entrepreneurs are forced to sign over many of their businesses to third-rate operators, production plummets. This and other misguided policies cause more and more businesses to go belly-up.

Ultimately, those in power pass Directive #10-289, nationalizing all intellectual property rights and decreeing that no one may leave a job or be fired, that all industrial concerns must remain in business, that “no new devices, inventions, products, or goods of any nature whatsoever, not now on the market, shall be produced, invented, manufactured or sold,” and more.

In short, bureaucrats pass policies that strangle production, then grant themselves emergency powers to deal with the fallout—as did Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, and today, Maduro.

So, whereas Marx equated all capitalists with cronies and con artists, Rand made an important distinction. True capitalists win when their customers win. And the society that leaves people free to create life-serving values and cultivate win-win relationships—capitalism—requires that every individual’s right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness is upheld.

Communism, as we’ll see, does not.

Slavery or Freedom?

Marx thought the source of the world’s problems was private property—specifically, that owned by the wealthy—and he aimed to abolish it. “[T]he theory of the Communists may be summed up in the single sentence: Abolition of private property,” he wrote.

Communists had been accused of ignoring the fact that private property is “the fruit of a man’s own labour” and “the groundwork of all personal freedom, activity and independence.” Not so, Marx responded:

Hard-won, self-acquired, self-earned property! Do you mean the property of the petty artisan and of the small peasant, a form of property that preceded the bourgeois form? There is no need to abolish that; the development of industry has to a great extent already destroyed it, and is still destroying it daily.

So a poor farmer’s plow is his, if he can keep it, implied Marx. But what if he pours his earnings into the purchase of a motorized tractor, and the earnings from that into a whole fleet of such tractors? What if he rises by dint of his own honest effort from poverty to wealth, as was happening all over America, even as Marx scribbled away? In fact, Americans were pulling themselves up by their bootstraps much earlier.

For instance, Benjamin Franklin, the tenth son of a soapmaker, became a printer, opened his own business, founded a newspaper and an almanac, and was so industrious and frugal that he could afford to retire at the age of forty-two. He then revolutionized our understanding of electricity and became, as historian Gordon Wood wrote, “the greatest diplomat America has ever had.” To this day, Franklin stands as a symbol of the fact that a free man may rise as high as his ambition will take him.

Marx, however, denied that such men exist. A person can be honest or wealthy, but not both. If he made a fortune, then by that fact alone, it was not “Hard-won, self-acquired, self-earned property!” Instead, it was “bourgeois private property.” And such “modern bourgeois private property is the final and most complete expression of the system of producing and appropriating products, that is based on class antagonisms, on the exploitation of the many by the few.” One might ask Marx: How does the investment of the entrepreneur who scrimps and saves constitute exploitation of anyone?

Ayn Rand asked this very question. Born in St. Petersburg in 1905, she witnessed firsthand the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution enacting Marx’s ideas. Her father’s pharmacy was forcibly taken by the Communist government. Then the Communists took their home and everything in it. True to Marx’s vision, they abolished private property—and they soon ground the entire country into unspeakable poverty.

Like John Locke and America’s Founding Fathers, Rand came to see that denying a man the right to his own property means denying his right to life. She wrote,

The right to life is the source of all rights—and the right to property is their only implementation. Without property rights, no other rights are possible. Since man has to sustain his life by his own effort, the man who has no right to the product of his effort has no means to sustain his life. The man who produces while others dispose of his product, is a slave.

Work takes time. Your time is your life. If someone takes the product of your work without your consent, he takes a part of your life without your consent. By violating your property rights, he violates your right to life. Insofar as you are forced to give up your life, you are a slave.

Rand recognized that, no matter how much you earn, your property is yours by right—because your life is yours by right. You may use or dispose of it as you wish, including opening a pharmacy or giving to charity. But to whatever extent you are forced or defrauded into forfeiting your rightful property—whether by a shady salesman, a dishonest employer, a political tyrant, or a democratically elected legislature—you are enslaved. That is exploitation.

And that is what Marx advocated. Property rights be damned. The collective must be empowered to redistribute wealth “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need.”

The practical consequences of this policy can be seen in the smoking debris of the 20th century, and in today’s headlines about Cuba and Venezuela. But anyone can run the experiment far more cheaply.

Suppose the company you work for adopted such a policy. Would you take on more responsibility if, instead of a raise, a bigger portion of your earnings would be given to your colleagues? How motivated would you be to stay late, to try harder, to create new products or services that would provide value to customers and generate wealth for your company? Wouldn’t it be better merely to coast, to let others shoulder the burden, to be an object of “need” instead of a person of “ability”?

Not only does a man have a moral right to the product of his own effort, Rand saw, but his ability to benefit from that effort incentivizes him to create more of what he and other people value.

So, whereas Marx held that property rights are responsible for keeping people in poverty, Rand saw that they are the precondition of wealth and plenty. And whereas Marx held that property rights are the root of exploitation, Rand saw that they are what keep a man from being exploited, the only practical implementation of his right to life.

Class War or Voluntary Association?

Marx’s “solution” to the “problem” of property rights was the most destructive aspect of his manifesto. It was also the most Orwellian. He held that the only path to peace is war: In order to abolish private property and thereby end exploitation, the poor must rise up and expropriate the rich—by any means necessary. Their victory requires a “more or less veiled civil war, raging within existing society, up to the point where that war breaks out into open revolution, and where the violent overthrow of the bourgeoisie lays the foundation for the sway of the proletariat.”

Rand saw this for what it is—a call for the barbaric violation of rights. And, in the streets of Russia, she witnessed the “violent overthrow” Marx had prescribed. It was bloody, but when the “sway of the proletariat” was firmly established under Lenin, and later Stalin, it only became more brutal.

In 1925, at a farewell gathering before Rand escaped to America, a young Russian said to her: “When you get there, tell them that Russia is a huge cemetery and that we are all dying.” Rand’s first and most autobiographical novel, We the Living, did just that. But not until 1957, with Atlas Shrugged, did she spell out in full detail why might does not make right.

To force a man to drop his own mind and to accept your will as a substitute, with a gun in place of a syllogism, with terror in place of proof, and death as the final argument—is to attempt to exist in defiance of reality. Reality demands of man that he act for his own rational interest; your gun demands of him that he act against it. Reality threatens man with death if he does not act on his rational judgment; you threaten him with death if he does. You place him into a world where the price of his life is the surrender of all the virtues required by life—and death by a process of gradual destruction is all that you and your system will achieve, when death is made to be the ruling power, the winning argument in a society of men.

Whereas Marx held that achieving a civil society requires class war, Rand recognized that force is only ever appropriate in response to those who initiate it. A man has a right to his own life and property, and he likewise has a right to protect his life and property against any vandal, slave driver, or dictator who threatens them.

***

University professors are leading the charge to inculcate more “diversity” inside and outside the academy. They focus almost exclusively on unchosen characteristics such as gender, sexual orientation, and race—as if a person’s genitalia, sexual preferences, or skin color determines the content of his mind and character. In fact, they are adapting the same old Marxist ideas of class war to instigate race and gender wars.

That’s ironic because, in the context of higher education, the only diversity that matters is that of interests and ideas. And it’s hard to imagine two thinkers more divergent than Karl Marx and Ayn Rand.

So, whether professors want to promote diversity or just better prepare students for life in civil society, they ought to introduce some counterpoint into the curriculum: Teach Atlas Shrugged alongside The Communist Manifesto.

Author’s note: This piece is dedicated to the Venezuelan students I recently met, whose schools teach Marxism while their country sinks beneath a tyrant who practices it.